PMW 2025-005 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

PMW 2025-005 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

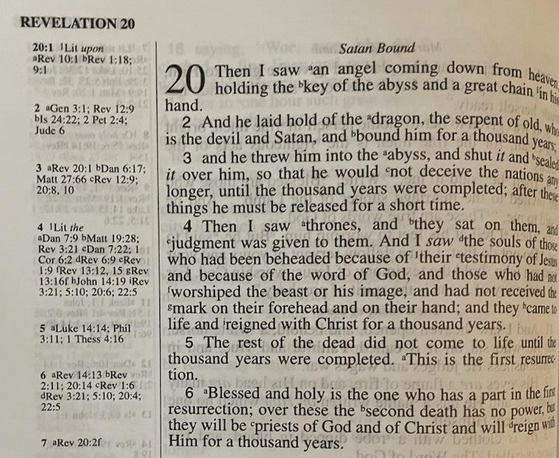

I am continuing some reflection upon the millennial passage in Revelation 20. Rightly or wrongly, this text dominates the eschatological discussion. Before reading this article, you will need to read the preceding one.

The Issues Impacted

First, I originally held that two groups were in view Revelation 20:4. I held the common Augustinian view that the martyrs represent deceased Christians in heaven (the Church Triumphant) and the confessors represent living saints on the earth (the Church Militant). And together these two groups picture all Christians throughout Church history. I no longer accept this interpretation.

Second, I also previously held that the fact that they “came to life and reigned with Christ” (Rev 20:4c) portrayed the new birth experience, where the Christian arises from spiritual death to sit with Christ in heavenly places. I still believe this doctrinal position, for it is taught in various places in Scripture (see especially Eph 2). But I do not believe this is a proper exegetical position here in Revelation 20. In other words, I now believe that this view is good theology but bad exegesis — if we try to draw it from Revelation 20.

Third, I previously held that “the rest of the dead” who “did not come to life until the thousand years were completed” (Rev 20:5) pointed to the bodily resurrection of all the unsaved at the end of history, as a part of the general resurrection of all men. As an orthodox Christian I do, of course, believe that John teaches a general resurrection of all men. He even teaches it in Revelation 20. But I now believe he holds off on that until verses 11–15.

Understanding the Olivet Discourse

By Ken Gentry

This 5 DVD lecture set was filmed at a Bible Conference in Florida. It explains the entire Olivet Discourse in Matt. 24–25 from the (orthodox) preterist perspective. This lecture series begins by carefully analyzing Matt. 24:3, which establishes the two-part structure of the Discourse. It shows that the first section of the Discourse (Matt. 24:4–35) deals with the coming destruction of the temple and Jerusalem in AD 70. This important prophetic event is also theologically linked to the Final Judgment at the end of history, toward which AD 70 is a distant pointer.

For more educational materials: www. KennethGentry.com

The Problem Created

In Revelation John takes images from the Old Testament Scriptures — often reworking, restructuring, and reapplying them. He is effectively mining the Scriptures for material that he can use to construct his own symbolic world. His symbolic world primarily dramatically presents the first century Judeo-Christian historical experience leading up to and including the destruction of the temple in A.D. 70.

As Revelation teaches, A.D. 70 changes everything in redemptive-history: it ends biblical Judaism (after 1500 years Israel can no longer offer sacrifices as required by her Scriptures; Judaism becomes rabbinic Judaism, a mutated form of biblical religion), stops animal sacrifices (Heb 8:6; 9:11–28), universalizes the true religion (Jn 4:20–24; Eph 2:11–19), enlarges the people of God (Ro 11:17; Gal 3:29), and initiates the new creation (2Co 5:17; Gal 6:15; see Ch. 15 below).

Thus, in A.D. 70 Christianity finally separates from her parent religion, never to return. As dispensationalist theologian David K. Lowery observes: “It is generally accepted that Jewish Christians maintained connections with Judaism to one degree or another before the revolt and subsequent destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple in A.D. 70.” But after that event Christians no longer conceive of themselves as a sect of the Jews, but understand that in Christ “the old things passed away; behold, new things have come” (2Co 5:17). This effectively parallels the message of Hebrews, where the writer warns Jewish Christians against apostatizing back into Judaism (Heb 2:1–4; 4:1–11; 10:19-39) because the old covenant is ending (Heb 8:13) as Christ introduces the final stage of redemptive-history (Heb 1:1–13). Old covenant Israel is nearing the time of God’s judgment as the new covenant is dramatically secured in the destruction of Jerusalem (Heb 12:18–29; Matt 3:11–12; 8:11–12; 21:43 –45; 23:34— 24:2).

Navigating the Book of Revelation (by Ken Gentry)

Technical studies on key issues in Revelation, including the seven-sealed scroll, the cast out temple, Jewish persecution of Christianity, the Babylonian Harlot, and more.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

One distinguishing characteristic of Revelation involves its awkward grammar, which does not follow standard Greek structure and patterns. John self-consciously takes on the mantel of the classical prophets (much like John the Baptist), and in doing so he structures his grammar to mimic the Hebrew of the old covenant prophets, whose material he abundantly adopts, often reapplying them. Several scholars note that John’s awkward Hebraicisms tend to occur in his visionary material rather than in his other sections.

This is all by design; it is not due to John’s inability to write Greek (see the Greek of his Gospel and Epistles for more standard Greek form). He is “becoming” an Old Testament prophet to take up his Old Testament-like challenge to Israel. Thus, John approaches Israel like Isaiah (see especially Isa 1), Jeremiah (see especially Jer 2–3), and Ezekiel (see especially Eze 2—6, 16). In fact, he organizes his material around Ezekiel’s structure — which explains so many specific parallels to Ezekiel:

Eze 1 = Rev 1

Eze 2 = Rev 5 (10)

Eze 9–10 = Rev 7–8

Eze 16, 23 = Rev 17

Eze 26–28 = Rev 18

Eze 38–39 = Rev 19–20

Eze 40–48 = Rev 21–22 (11)

But now, what are my changes? And how are they significant? You will have to give me some time to figure this out. So, let’s wait until the next article. I ought to be tanned, rested, and ready by then.

THE APOCALYPSE OF JOHN

by Milton S. Terry

This book is Terry’s preterist commentary on the Book of Revelation. It was originally the last half of his much larger work, Biblical Apocalyptics. It is deeply-exegetical, tightly-argued, and clearly-presented.

For more study materials: https://www.kennethgentry.com/

Wasn’t John the Baptist the last warning prophet for the coming Day of the Lord?

He was the last of the prophets of the old covenant.

If so… and I do believe he was… then how could John the apostle also be a prophet of the Old Testament? He did prophecy 1000 year reign with Christ here on earth. No where in Old Testament speaks of this specific prophecy… especially stating it would be a first resurrection and then satan is loosed and then a final judgment resurrection.

John the Apostle was a prophet of the NT order.

I misstated. I mean how could John the apostle be the last Old Covenant prophet? Seeing that the temple was the end of the old covenant and it’s practicing of the law

I don’t see John the Apostle as an old covenant prophet. Jesus established the new covenant with his disciples in the Upper Room.